Here’s a question for President Barack Obama’s re-election team. It could influence the outcome of this year’s election:

How do they get the "we" back?

We all remember how Obama broke new ground in the 2008 campaign by using social media as a powerful political tool. Obama’s campaign created an expansive Internet platform, MyBarackObama.com, that gave supporters tools to organize themselves, create communities, raise money and induce people to not only to vote but to actively support the Obama campaign. What emerged was an unprecedented force, 13 million supporters connected to one another over the Internet, all driving toward one goal, the election of Obama.

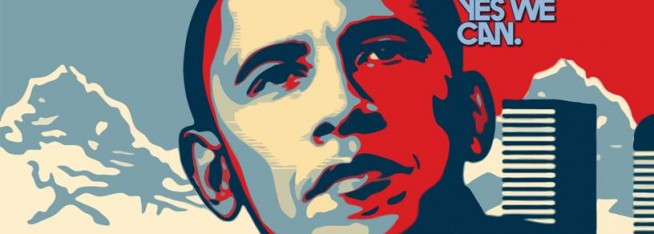

When they chanted "Yes We Can," it wasn’t just a message of hope for the future; it was a confirmation statement of collective power. They weren’t waiting to be told what to do; they were actively engaged, calling friends to come to events, to learn what was at stake, contribute ideas, and help out in some way. The power of "we" was awesome to behold. The "we" not only raised hope for people; it raised unprecedented sums of money for the old-fashioned campaign on the ground.

But this time, "Yes We Can" has been replaced by a new modus operandi for the Obama campaign. It’s "We know you."

The Democrats are investing heavily in what’s called Big Data to give them significant new insights into the everyday behavior of each one of their supporters. Big Data allows companies, or political campaigns, to probe and analyze information about you — your friends, your shopping habits, what type of events you go to and when, what issues you care about. With this information, they can presumably be more accurate in sending messages out over email, or in identifying the trigger points that send you to events and get you to donate money.

But whatever happened to power of the people? Whatever happened to the "we"? We haven’t heard about it since the 2008 victory. "They built the largest online community in the history of the presidency," says Andrew Rasiej, founder of Personal Democracy Media, which tracks the intersection of technology and politics. "But then they stopped talking to them and engaging them" — that is, until they called in recently with a pitch for money.

Obama did make some efforts to be the first Internet president, with a Twitter feed, a blog, and the Internet version of the traditional town hall. He launched an open government initiative with the aim of cutting the influence of special interests and giving the public more influence over decisions that affect their lives. Compared with other governments around the world, the U.S. government sets the gold standard for government openness.

And yet, four years after Obama was elected, nothing much has changed. The same rules apply: Give me your vote and I will rule. Rasiej is disappointed: "Lots of us believe he squandered the massive political constituency that was drawn to his message of hope and change." The 13 million supporters, for instance, could have helped Obama by lobbying their congressmen to back the health care legislation. Yet Rasiej thinks the White House, and in particular Obama’s first chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, didn’t believe in the power of "we." "They went back to the bully pulpit of the presidency. They literally put on the armor of 20th century communications."

That attitude seems to have influenced the 2012 campaign.

"It’s a completely different campaign," says Nomiki Konst, 28. In 2008, she helped to help to raise millions of dollars for Obama by organizing events in Los Angeles with some big names in music and movies. "It was inspiring," she said. "When someone says you have the ability to do what you want, it gave me the power and the potential to do so much more. I could relay that inspiration to others." This time, "it’s a traditional top-down, managed campaign." It now takes months to approve plans for events. "They’re putting handcuffs on people," said Konst, who served as national co-chair of Gen 44, the Obama campaign’s fundraising arm for young people. She got so frustrated that she resigned in November 2011.

In Los Angeles, 33-year-old film executive Haroon "Boon" Saleem worked hard for Obama in 2008 to galvanize young professionals, with comedy nights, debate watching parties, movie nights where you could meet successful movie and TV celebrities. They spread the word, made friends, and helped to raise $1.6 million for the campaign. The ideas didn’t come from the Obama organization. "We just did it," says Saleem. This time, Saleem is planning to help out, but he can feel the resentment in the young supporters: "I know a huge number of people who are unhappy," said Saleem. "They wanted to be connected and involved but they weren’t."

The Obama campaign may think that they don’t need to worry about youth support. A new national poll of America’s 18- to 29- year-olds by Harvard’s Institute of Politics shows that Barack Obama now leads his likely Republican opponent Mitt Romney a 17 point margin, a gain of six percentage points since November 2011. But will young people be as keen to raise money and connect with friends to support the president? Will they go out and vote in huge numbers, as they did in 2008, when an extra 2 million Americans under 30 voted, mostly for Obama?

A senior figure in the Obama campaign tells me that they can’t depend on self-organization in the way same that they did in 2008. For one thing, the Obama campaign cannot do or say anything that compromises the president’s first term. As an incumbent, he needs to be more cautious in 2008 when he was a long-shot candidate.

But that shouldn’t stop the campaign from tapping into the power of self-organization. The Obama campaign itself showed in 2008 that you can let people create their own communities without hurting the integrity of the core message. The Obama campaign set out clear rules of engagement that prohibited, for instance, trash talking about Sarah Palin’s family, said Rahaf Harfoush, who worked on Obama’s social media campaign and then wrote a book about it. Whenever supporters said something that didn’t jive with Obama’s message, the campaign made it clear that the outlier didn’t speak for Obama. This time, the Obama campaign could write a clear rider/disclosure statement to the world that the communities do not necessarily reflect the views of the campaign. The community itself could register its approval, or disapproval, of statements by members.

Obama’s digital people also point out that they don’t need to rely so heavily on MyObama.com because there are so many other social networking tools out there. Yet as Harfoush point out, "facebook is not equipped to help people organize, as MyBo was."

If the campaign doesn’t return to its winning ways, and fast, it risks continuing to isolate itself (or even alienate) youth. Youth don’t want to be organized; they want to take action themselves. They want to participate, not be passive recipients of campaign instructions. They want to take initiatives rather than be told what to do from all-knowing campaign strategists. The Tea Party understands this; Obama once did too.

So if the Obama campaign wants to get back to the "we," what should it do?

One: Let go. Instead of telling people what to do, let them create their own communities to make friends and contacts, and raise money. Start a conversation. Let them contribute in their own way, without instructions from the top. There are plenty of ways to contain the outliers, and the community will be far more powerful than any top-down hierarchy can be. "It’s important for people outside the campaign to disseminate messages so it feels authentic," said Saleem. "It helps to hear one of your friends talk about the successes."

Two: Recreate the platform. In 2008, the Obama campaign’s platform, MyBarackObama.com, was wildly successful. By election day, more than 35,000 groups had formed to support Mr. Obama, and they had organized more than 200,000 events and raised vast sums of money. It worked then. Why not now?

Three: Engage with them on the issues: Start a conversation with them about the issues they care about, like contraception, says Saleem: "It’s a really good way to draw in disenfranchised millennials than Obama will need if he wants to win."