HUNDREDS of millions of people have joined social networks, swapping news on Facebook, spouting opinions on Twitter or amassing professional contacts on LinkedIn. Rather fewer may have realised that they work for one. Companies, in essence, are collections of people, with ideas and expertise of different types. The trick of business success lies in harnessing these human qualities.

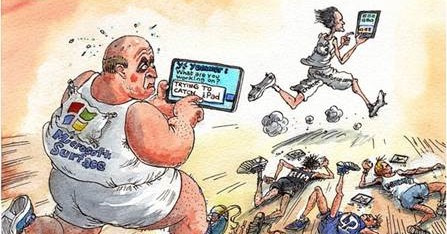

Lots of software companies are trying to help other companies do just that—and thus, in the phrase of the moment, to become “Facebook for the enterprise”. In business as well as private life, young companies have been making much of the running, with some older big beasts of the technology industry straining to catch up. This month it was reported that Microsoft had agreed to buy one of these upstarts, Yammer, which is less than four years old but boasts more than 5m users in companies, for $1.2 billion. Neither side is commenting on the report.

If it is true, it suggests that Microsoft wants (or needs) something more than its own social product for businesses, SharePoint. Mark McDonald of Gartner, a research company, sees the putative purchase as “an industry consolidation play. With demand increasing, you want as much of the platform as possible.” And demand is rising quickly. A report this week by IDC, another research firm, said that most sellers of enterprise social software enjoyed double-digit revenue growth last year. It reckoned that Yammer’s revenue grew by a giddy 132%, to $22.3m.

At $1.2 billion Yammer would be worth about as much as Jive Software, an older, bigger youngster that was floated on the stockmarket last year. That would mark a nice return for the venture capitalists who have invested $142m in Yammer. In February Techcrunch, an industry website, reported that in Yammer’s most recent financing round, in January, it was valued at $500m-600m. Investors have been recalculating Jive’s worth as a result: its share price has risen by a quarter since reports of Microsoft’s bid for Yammer appeared.

Bring your own network

Social networks for companies mimic the methods of public ones, which lots of firms already use to push their wares and to listen to what people say about them. In forums that look like Twitter feeds or Facebook pages, sales teams can share leads and information about clients (some of it gleaned from profiles on public networks), ask for and get speedy approval of discounts and slap one another virtually on the back for clinching a deal. Groups can be formed for specific projects. Documents can be shared. Flows of work can be organised. Expertise can be sought and pooled.

Information and opinion seem to travel faster than with older forms of communication. Chief executives claim that their posts draw quick responses from staff—prompting them to answer in return. Internal networks generate useful data of their own—such as whose ideas are most passed on or praised. And the public sector is also becoming more social in the hope of becoming more efficient. On June 19th Socialtext, which specialises in networks run on its customers’ premises (rather than outside, in the “cloud”), said it had won a contract with America’s Department of Housing and Urban Development.

In part, companies are setting up social networks because they have a generation of employees who are used to communicating this way. To them, not using social networks at the office (or, just as likely, on the road) would be as antiquated an idea as not using smartphones.

At the headquarters in London of Burberry, a British maker of fashionable clothes, 70% of the staff are under 30. “I grew up in a physical world, speaking English,” says Angela Ahrendts, Burberry’s chief executive. “They grew up in a digital world, speaking social.” Burberry’s choice of network is Chatter, which belongs to Salesforce.com, a cloud-computing firm; more than 6,000 of Burberry’s 9,500 staff are on it. Marc Benioff, Salesforce’s boss, is the most prominent evangelist for the “social enterprise”, in which the principles of social networks permeate the whole company, connecting employees, customers and even physical products.

For Yammer, “viral” adoption has been the key to its success. People can set up their own networks easily, even without the IT department’s blessing. Its basic service is free. Payment is due only from groups that want more file storage or support. With luck, popularity will speak for itself and members will be generating a lot of useful material. Around 15-20% of free users end up being paid for. Perhaps not surprisingly, Yammer is not everyone’s cup of tea. Eugene Lee, Socialtext’s chief executive, says Yammer’s model is one “that end-users and venture capitalists love and that IT and finance hate.”

Even in a closed corporate network, people have to be careful about what they say about whom. At Deloitte, a business-advisory firm, which has more than 57,000 people in its global Yammer network, clients’ names may not be mentioned at all. Security and confidentiality matter all the more when networks spread beyond the borders of a firm, as more and more of them do, to include suppliers or customers. If a law firm, say, sets up a group that includes its partners and client A, it cannot let on that it also works for client B.

Not every company is ready to let social networks under its roof. A recent study by Gartner of more than 250 organisations classed 35% of them as “fearful”. But having a corporate version of Facebook may make people less likely to talk loosely about work on the real thing. Microsoft and others are betting that more bosses will start to think that way.