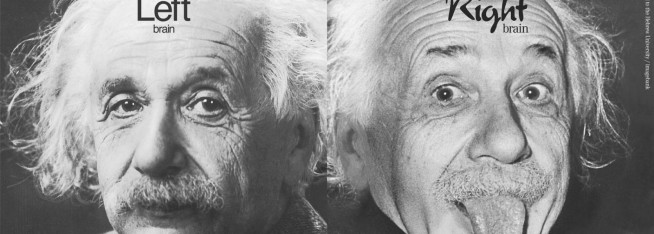

We all know that the human brain is split into two hemispheres: the left brain provides analytic thinking and the right brain provides creative thinking. The key to unlocking innovation is to apply both types of thinking with equal authority and in the right order. Fashion brands are a great example of how this model can work – the world’s most successful fashion brands are all run equally by a CEO (left brain) and Creative Director (right brain).

However, many traditional organisations tend to “stick with what they know” and keep doing what they’ve always done. Particularly in tough economic periods, the tendency is to rationalise and not stray outside of “tried and tested” ways of working. Inevitably, this leads to stagnation, which is a one way ticket to being overtaken by your competitors – Toyota and Honda broke into and took over General Motor’s huge market share in the US simply because they committed to innovation while GM stuck with their “tried and tested” operations.

Clearly, investing in innovation is just good business sense.

So how do we integrate both left and right brain thinking in a way that will unlock true innovation? In order for creative ideas to be effective we need to apply left brain (strategy) and right brain (ideas) thinking in the right order.

Rigby, D.K., Gruver, K. & Allen, J. 2009 ‘Innovation in Turbulent Times’, Harvard Business Review, June 2009 Vol. 87, No. 6, pp.79-86

Hi Amer,

I really like this approach and have seen the obvious benefits both here at Deepend and in the industry at large. That said, I can’t help but think its a very traditional ‘strategic’ or linear approach to thinking. In Malcolm Gladwell’s book Blink, (The power of thinking without thinking) he highlights that our highly evolved brains, through years of experience, have become experts at ‘thin-slicing’ (ie. being able to process an incredible amount of detailed information without really understanding ‘why’ or the ‘how’; it happens in our subconscious. He believes, and I mirror his POV, is that the concept of intuitive thinking (thinking without reasoning) is really quite a rational process but just carried out really quickly. (through thin-slicing) This combination of both Left and Right brains working at the same time creates new ideas and innovations concurrently rather than a more traditional linear process.

Sometimes what your ‘gut-feeling’ is… ie. your first idea… is quite often your best.

Blink is a great read! Another Malcolm Gladwell book worth checking out is The Tipping Point on what starts epidemics.

Or if you want an Aussie perspective on the human brain read “What Makes Us Tick” by Social Researcher Hugh Mackay.

Sorry i missed the session too, sounds interesting and thanks for the model – And on Gladwell, his latest, ‘Outliers’ is probably worth a look too. In a nutshell, it’s the circumstances people find themselves in rather than any individual trait they have, that leads to great things happening.

And a counter to his ‘find the mavens’ line of thought in Tipping Point, is the idea of accidental influentials by Duncan Watts. I first heard about the idea a few years back in an hbr podcast.

Here’s a link to a fast company article.

http://www.fastcompany.com/641124/tipping-point-toast

Also I’m not sure about the science of the left brain – right brain argument. Studies show there are two types of creativity, adaptive and innovative. Adaptive says ‘what have we got, how can we improve it, how have we done this before, etc.’, innovative says ‘why are we doing this anyway, couldn’t we do this instead, etc.’.

Most scientific progress has been made through adaptive creativity, though innovative creativity provides leaps of thought and different perspectives that are essential for new thinking to take place.

On quick thinking being best (Blink’s core thought), I saw a tv programme the other night about identity line-ups for crime suspects that showed the shorter time people had to choose, and the longer time between incident and trying to identify a culprit, the more accurate the results – interestingly witnesses weren’t asked to say which one the perpetrator was, but instead they were asked to rate each image on what they thought the probability was that that person in the photograph was in fact the perpetrator.